Direct Approach in Ukraine: Opening a dialogue on violence through film

Direct Approach in Ukraine: Opening a dialogue on violence through film

Interview with conceptual artist Stine Marie Jacobsen

As part of Danish Cultural Institute’s new focus on Ukraine, this spring we invited conceptual artist Stine Marie Jacobsen to create a Direct Approach workshop in collaboration with Ukrainian partners in the port city of Mariupol, in the south-eastern part of the country.

Her anti-violence project Direct Approach gives a platform to explore, discuss and reframe personal encounters with violence, that can be implied in different peace building initiatives and open conversations on sensitive topics. The process always begins with meetings and individual interviews, where the participants each select a scene of cinematic violence, that has made an impact. In the scene they are asked to choose a role – victim, perpetrator or bystander – to play in a retelling of the story. This way the person gets a chance to reflect on the impact of the violence and how one chooses to act in the situation.

The attack in Mariupol

In 2018 one of the main cultural venues in Mariupol “Platforma TU!” was attacked by radical right-wing young people, that broke in during a LGBT-friendly concert, injured people, destroyed furniture and musical instruments.

The incident was later silenced by the local administration and is still under the investigation process. Together with local partners in Mariupol, DCI contributes to open a public discussion around the notion of violence.

Art with social impact

We talked to Stine Marie Jacobsen during the project in Mariupol, where she has partnered with the Ukrainian film director Yulia Hontaruk, known from her clear-cut documentary “Ten Seconds” about how the peaceful life of the people in Mariupol was invaded by the war.

– You have worked with the Direct Approach project in several parts of the world, and now you are in Ukraine. What is special for the project in Mariupol?

During a research trip in March 2019 to Mariupol, I met peace builder Pavlo Kutana from the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) and Ukrainian film director Yulia Hontaruk, who both have been engaged in the Russian-Ukrainian war, since it started in 2014.

Yulia Hontaruk has been filming it, and Pablo Kutana has been doing peace building work. With Hontaruk I’m also working together with sound guy Andrii Nidzelskyi, DOP Serhiy Stetsenko, film editor Mykola Bazarkin and from the Danish Cultural Institute, Yuliya Zakolyabina, who managed the whole project amazingly.

Special for Mariupol was, that Hontaruk suggested, that we film the interview. Until now the first interviews were always only sound recorded. But she wanted to see and hear their reactions to my questions, and we decided, that we could cut between their interview and remade film scene respectfully.

How much did you know about the conflicts in Ukraine, or the tragic attacks in Mariupol, before you started working on this project?

I knew very little. I read the news about the Euromaidan and the annexation of Crimea in 2014, but did not know what the current situation is, and how the violent conflict has developed since. Although Mariupol is situated in the Donetsk region, it is a controlled by Ukrainian government, so they don’t have the same issues like in the separatist regions of Donetsk and Luhansk.

How do you prepare for a project like this?

By being super alert to any information given through organisational briefings, conversations with locals and diverse news reading. And keep asking around, and getting other and as many perspectives as possible. People like a mayor or hosts will want to escort you around and show you the best. From my experience in Ukraine, the heightened nationalistic rhetoric there makes people blame Russia or the Russian separatists very easily, whether or not that’s the truth.

Have you chosen a specific concept for the project in Mariupol?

Yes, I estimated, that it would be best to not do a workshop, but instead do 1:1 interviews and remakes of film scenes in Mariupol in order to have a local film team and educators learn the method.

So, I first interviewed Kutana from DRC during my research trip, who then in April passed on the method to Hontaruk by interviewing our first 3 participants, and then Hontaruk interviewed our last 8. Out of the 11 interviewed people, we selected 3 for re-filming their film scenes. One of the participants, Maria Pronina, a refugee within her own country (internally displaced person (IDP), psychologist and an art therapist.

The Direct Approach method asks people to retell from their memory a violent film scene, and it is not a suitable method for people, who have just experienced real violence, but more suitable for teenagers or adults, who live in “post-violence” societies really. So in a way, it’s not yet suited for Mariupol, as they live only 20 km from the frontline, and there are a lot of displaced Ukrainians living here. But with a careful participant selection and making sure, that we don’t select anyone suffering from trauma, it’s responsible to use the method. We spoke to citizens in Mariupol, who liked the method and wanted or were ready to share their insights and experiences on violence.

“The Direct Approach method helps participants process their former experience and knowledge from a new angle” Yulia Zakolyabina says and continues: “This method makes them realize other things about their former experiences, that they hadn’t considered before”.

With your experience from approaching violence in many different societies, what is your view on how violence and the war have influenced a society like Mariupol?

Violence has shaken and isolated Mariupol, but its people are not weakened. Far from it. I feel that everyone is smiling every time, they heard me speak English, and it’s as if people are super happy to meet me — a tourist. It signals to them, that Europe has not forgotten them, and more tourists may come.

They will fight hard to keep Mariupol Ukrainian. However, a much more concerning thing, are the many families in east Ukraine suffering from internal conflict, because of political divergent opinions within close relations. Maybe a father is Pro-Russia and mother Pro-Ukrainian. There is a lot of focus on patriotism these days in Ukraine and talking about language. What to do in these cases?

It is similar to other places, that have had civil wars such as Colombia and Lebanon. I feel the pain and the raised nervousness, which is compensated and released in amazing friendships. People are very connected in conflict zones and extremely respectful to each other’s pains. Something, I think, is lacking in so-called welfare societies.

What is your impression of the city, and of the situation for (young) people in Mariupol?

The city needs to create new cultural environments and possibilities to make young people stay. The cultural place Platforma TU is really doing pioneering work in Mariupol. I met many artists and activists there. The psychologist Maria Pronina is also connected to the place, and I hope, that she could do a Direct Approach film workshop for teenagers in the future.

Pavlo Kutana also knows the Platforma TU people. Pavlo started working for DRC after the shelling of Mariupol began in January/February 2015. After the military attack he decided to change his life and start helping people. He now works in the Protection Department of DRC, where they have different activities such as: individual child assistance, implementing of psycho social support for affected communities, for schools and technical colleges. Kutana’s department just finished a big and important Needs Assessment Report on child mine victim survivors. This report shows gaps in the government assistance on this sphere. DRC are continuously working with mine victim assistance project and provide case management to the affected families.

The Ukrainian crew

Can you say a little bit about what is characteristic for Yulia Hontaruk’s work, and for the Ukrainian film crews take on your project?

I am very impressed by Yuliya Hontaruk’s cinematic and documentary work, and that’s why I asked her to work with me. Yuliya is very direct in her style 🙂 It’s not often, that you meet a woman of her caliber. She literally films directly in the trenches with soldiers, while they’re shelling their enemies. With the upmost respect and sensitivity, she asks people to speak directly to her camera and share their stories with viewers. And at no time you have the feeling that she is filming something she shouldn’t. That’s because she knows and understands them. She is part of the conflict.

Yulia Hontaruk likes my Direct Approach project, because she usually doesn’t get to work the same way, psychologically deeper with people, where they can change some inner cognitive patterns. Everyone in the team was very surprised, how complex a conversation the method questions could generate, and I think, they all also just really liked the concept of retelling a film scene from memory and that is then our script.

Direct Approach is very different than Hontaruk’s documentary “Ten Seconds”, because it’s much more direct than Direct Approach! As one of her characters says “it’s important to show the reality as it is”. Yuliya was filming in Mariupol, when the shelling began in January 2015. So she was in the war zone when everything was happening. It’s really an important documentary film to watch. Here it is online: http://10seconds.docuspace.org/eng/

My project is about visual literacy and using cinema as a tool to talk about something, that you might not want to talk about directly. So my project is actually indirect. I created the project in Germany, because I noticed, that it was difficult to talk about the nazi regime and past violence, and also I did not want to link any population and nationality with violence, because it would be violently judging them. So I came up with the indirect method, so that I would not have to categorize anyone, but the participants could position themselves.

How did you select the participants for the project, and how did they or other people in the community react to it?

We interviewed 11 people between the ages 15 and 55 years old and remade three film scenes.

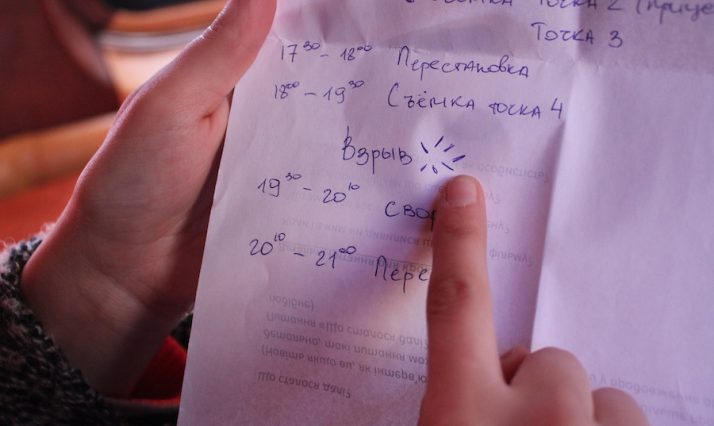

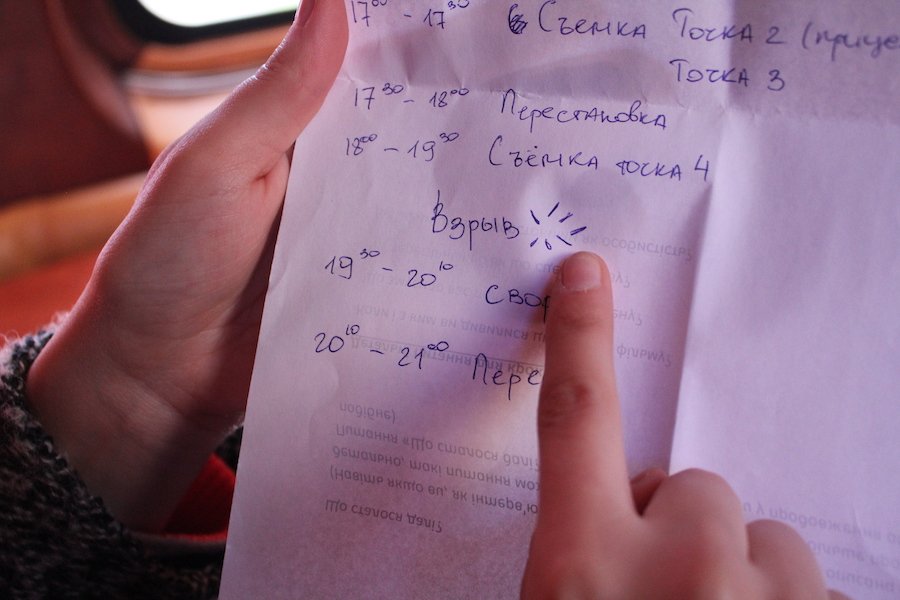

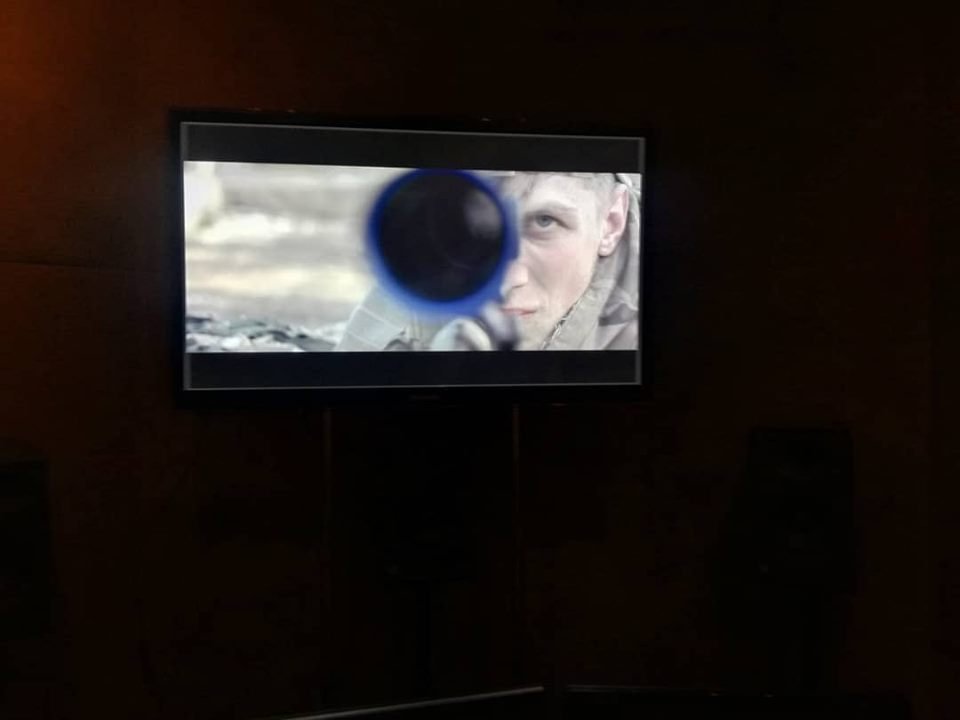

Maria Pronina (Маша Пронина) retold a torture scene from a BBC TV series called Utopia from 2013. Irina Prudkova (Ирина Прудкова) retold a scene about bullying from a Russian movie called “Scarecrow” (Russian: Чучело or Chuchelo) from 1984. Alexsey Kelt (Алексей Кельт) retold a scene from “American Sniper” and talked about patriotisme.

The film themes were very varied from war and torture to family problems, self-inflicted pain and bullying. There were of course local films mentioned, but in general American Hollywood violence movies are mentioned, also worldwide.

People immediately understood the project. Some even made jokes about, how it resembled Gondry’s “Please Be Kind Rewind”, but generally they liked, that they weren’t asked about their private stories (directly).

They have been very open and willing to share their experiences with violence. Some IDPs have moved to western cities and occasionally return, but to protect themselves and their families, they are sometimes careful with media projects to keep from being targeted by either side.

Ukrainian nationalists actually published a list of people throughout Ukraine, who ‘cooperated with separatists’ in sharing stories or to gain access to the region. Families living there have also been targeted with bombings and attacks, if they cooperate with media. But the people we met in Mariupol seemed not “shy” at all.

We interviewed and worked closer with a former young veteran soldier, a young psychologist and middle-aged woman who is a former journalist – and they were all three very balanced and suitable for the project. The young psychologist Maria Pronina I hope could at some point do a workshop for teenagers and the film team a film workshop for teenagers.

Do you think the violence of the war still influence the city, and the view of the world of the people of Mariupol?

Of course. It’s not long ago since there were bombings here in Mariupol, and the municipality is still black from burning. Hanging on it is a flag, that says “Mariupol is Ukraine”. We are only 20 km away from the frontline, where they bomb every night.

What is your impression of the thoughts of the younger generation of Ukrainians for the future – for the society or for themselves?

Most young people in Mariupol are worried about the war reaching them in the city, and that

no-one will help, if that happen. They feel right now devastated with the new president elected, and in general that they can’t do anything about the political situation, and that Ukraine is in a bit of a “Catch-22”. The catch 22 means, that if we call it a war (right now it’s called a “violent conflict”), they fear, that US and EU will turn their backs to them, and Russia will take over Ukraine. Someone even brought up, that nobody cares about Ukraine, and that’s why Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was never resolved – who shot it down in 2014 …

Danish Cultural Institute’s activities in Ukraine

In 2018 Danish Cultural Institute (DCI) started to have activities in Ukraine. With 44 million citizens, the country is among the largest in Europe, and is the geographical link between Eastern and Western Europe. Since the 2014 “Revolution of Dignity” young Ukrainians across the country have been developing new ways of thinking, promoting anti-corruption, citizen participation and local communities.

Interview by Malene K. Holm